Abstract¶

CCore is a development platform. Its primary purpose is a real-time embedded development, but it also a great platform for a usual host development.

CCore gives a more professional language support for C++ development, than a standard C++ library, with greater attention to details of implementation, efficiency, robustness and derivability. It is also more “encyclopedic”.

Another important CCore mission: it opens the power of C++ to the system development. It also eliminates borders between system and application development, bringing methods, custom to system development, to the application level and back. It also provides a great support for the network and distributed development.

CCore brief¶

Many years ago I had started this project … Ab ovo

CCore uses an advanced memory manager … Heap

CCore provides Printf() print facility … Printf()

CCore uses an advanced exception handling pattern … Exceptions

One of the most useful invention, implemented in CCore, is DDL … DDL

CCore provides an advanced synchronization basis … Synchronization

CCore implements the Packets – infrastructure for the mass asynchonous request processing … Packets

CCore contains number of new network protocols and components … Networking

and much more …

CCore source contains many advanced C++ tricks, based on the latest C++ language features. No way I can describe all of them in this brief notes. So put your hands on …

The latest development stream is on github.

Ab ovo¶

Initially I had created a small real-time bare-metal core, mostly for experimental purpose. It was a kind of back-up for small tasks, where using a full-scale commercial RTS was too much expensive. But the core was well-made, and I decided continue development up to some extent. Eventually, this project become a solid platform, well suited for wide range of tasks, both host and embedded. I had a solid experience in software development (including embedded one) and I had a good vision, what do I want from a proper development platform. So far none of existing gives me even a fraction of what I want. So I am lovely developing CCore and use it for software development.

The main goal of CCore was to bring the fully-featured C++ to the embedded development. Up to present time there ara many projects, written on pure C. This is really weird situation. C is a primitive language, not suited for large scale projects, the practical ceil of C is 10000 LOC. Everything above this size must not be developed on pure C. In fact, C became a toxic language, polluting the software world. So CCore gives a better alternative. It is not only opens the door for C++, but provides well suited library support. In times CCore was started the standard C++ library was not develop well enough. For example, you could not put a non-copyrable object in the vector. Many important things, large or small, required for the professional development, are still missing in the standard library up to present.

One of the shameful lack in the modern C++ standard library is the absence of well developed printing tools. There are two options: the old-school C stdio and the C++ iostream. Both are crap. The first is not type-safe and type-driven, neither type-extendable. In iostream format options are included in the stream object. This is a principal architectural mistake. The printing streams itself are hard-to-use. Compare:

Printf(Con,"#8.16i;\n",12345);

Printf(Con,"#;\n",67890);

and:

cout << hex << setw(8) << setiosflags(ios::internal) << setfill('0') << 12345 << endl

<< dec << setiosflags(ios::right) << setfill(' ') ; // reset format flags

cout << 67890 << endl ;

So CCore includes its own printing subsystem, much more practical.

Both C and C++ provides a support for the dynamic memory allocation. Unfortunately, this support lacks some important features. What do I need from the heap?

First, speed and real-time properties for embedded systems.

Internal integrity check.

Memory block extension and shrinking.

Statistic counting.

So I included in CCore such a heap feature.

Usually embedded systems havily use networks for various purposes. That’s why a good support for network applications is required. CCore includes implementation of a proper infrastructre for that as well as an implementation of a set of new network protocols.

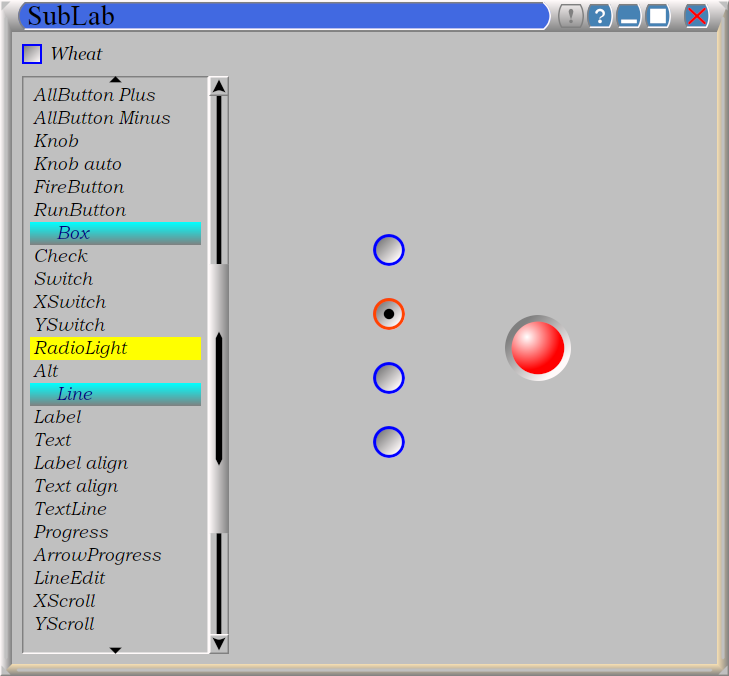

The latest big extension of CCore is a GUI development support. This part is almost finalized, but not yet documented.

Heap¶

CCore heap has the following features:

Best fit.

Heap selects a smallest available block of memory to satisfy an allocation request.

Fast, with real-time properties.

Integrity check.

If you try to use an invalid pointer as a heap function argument, it will be higly likely detected and abort will be called.

Extended interface.

Here is a list of heap functions:

void * TryMemAlloc(ulen len) noexcept; void * MemAlloc(ulen len); ulen MemLen(const void *mem); // mem may == 0 bool MemExtend(void *mem,ulen len); // mem may == 0 bool MemShrink(void *mem,ulen len); // mem may == 0 void MemFree(void *mem); // mem may == 0 void MemLim(ulen limit);

You can not only allocate and deallocate blocks of memory, but you can resize them in place (if possible). This is useful in the building of resizable arrays and other containers.

You can also set a memory allocation limit. This feature is useful for testing.

Heap has also some statistic functions, this allow to watch over the memory usage.

These features are highly valuable in any kind of software development.

Printf()¶

Printf() is similar to the C printf(). It works as the following:

int x = 12345 ;

Printf(Con,"x = #;\n\n",x);

The first argument is a printer object. In this case it is the console. The second is a format string. By tradition it is a null terminated string. After the format string an arbitrary number of arguments of any printable types may follow. They will be printed in places of format stems. Each format stem is a sequence like “#…;”. Between the starting ‘#’ symbol and the ending ‘;’ symbol options my be specified:

Printf(Con,"--- #10l; ---\n",12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10i; ---\n",12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10r; ---\n",12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #+10.5l; ---\n",12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #+10.hi; ---\n",12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.hi; ---\n",-12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2l; ---\n",12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2i; ---\n",12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2r; ---\n",12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2l; ---\n",-12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2i; ---\n",-12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2r; ---\n",-12345);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2l; ---\n",-12);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2i; ---\n",-12);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2r; ---\n",-12);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f4l; ---\n",12);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f4i; ---\n",12);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f4r; ---\n",12);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2l; ---\n",0);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2i; ---\n",0);

Printf(Con,"--- #10.f2r; ---\n",0);

and the output is:

--- 12345 ---

--- 0000012345 ---

--- 12345 ---

--- +343340 ---

--- +00003039h ---

--- -00003039h ---

--- 123.45 ---

--- 0000123.45 ---

--- 123.45 ---

--- -123.45 ---

--- -000123.45 ---

--- -123.45 ---

--- -0.12 ---

--- -000000.12 ---

--- -0.12 ---

--- 0.0012 ---

--- 00000.0012 ---

--- 0.0012 ---

--- 0.00 ---

--- 0000000.00 ---

--- 0.00 ---

Printf() ties together a printer object, a format string and printable objects. You can easily develope these kind of objects to match your particular needs.

Printer class¶

In general, to make a class a printer you have to define the following class elements:

class PrintToSomething

{

public:

using PrintOutType = PrintToSomething & ;

PrintOutType printRef() { return *this; }

void put(char ch);

void put(char ch,ulen len);

void put(const char *str,ulen len);

void flush();

};

In most cases, however, it’s better to inherit from the following base class for printer types:

class PrintBase : NoCopy

{

....

virtual PtrLen<char> do_provide(ulen hint_len)=0;

virtual void do_flush(char *ptr,ulen len)=0;

public:

using PrintOutType = PrintBase & ;

PrintOutType printRef() { return *this; }

// constructors

PrintBase();

~PrintBase();

// methods

....

};

You have to implement two virtual functions in a derived class to output printed characters to whatever you want.

Printable types¶

Making a type printable is simple like this:

struct IntPoint

{

int x;

int y;

....

// print object

void print(PrinterType &out) const

{

Printf(out,"(#;,#;)",x,y);

}

};

OR, if you need a printing options, like this:

struct PrintDumpOptType

{

....

void setDefault();

PrintDumpOptType() { setDefault(); }

PrintDumpOptType(const char *ptr,const char *lim);

//

// [width=0][.line_len=16]

//

};

template <UIntType UInt>

class PrintDump

{

PtrLen<const UInt> data;

public:

....

using PrintOptType = PrintDumpOptType ;

void print(PrinterType &out,PrintOptType opt) const;

};

Exceptions¶

CCore uses the special pattern to throw and catch exceptions:

All exception are of type CatchType, which is an empty structure:

try { .... } catch(CatchType) { }

To get exception notifications you have to define a special object:

try { ReportException report; .... } catch(CatchType) { }

To react on no-exceptions you have to call the special method guard():

try { ReportException report; { .... } report.guard(); } catch(CatchType) { }

To throw an exception use the function Printf():

Printf(Exception,"Shit happened"); // exception will be thrown by this call

OR:

Printf(NoException,"Shit happened, but we continue ..."); // no exception will be thrown by this call

Event if you don’t throw an exception, report object gets the exception text ans sets an internal flag. So later, when you call report.guard() an exception will be eventually thown.

Using this pattern you can safely handle exceptional situations in class destructors:

PrintFile::~PrintFile()

{

if( isOpened() )

{

FileMultiError errout;

soft_close(errout);

if( +errout )

{

Printf(NoException,"CCore::PrintFile::~PrintFile() : #;",errout);

}

}

}

No one glitch will be forgotten!

DDL¶

DDL expands as “Data Definition Language”. This is a textual language for representation of data. DDL files looks like:

type Bool = uint8 ;

Bool True = 1 ;

Bool False = 0 ;

struct FavElement

{

text title;

text path;

Bool section = False ;

Bool open = True ;

};

struct FavData

{

FavElement[] list;

ulen off = 0 ;

ulen cur = 0 ;

};

and like this:

//include <FavData.ddl>

FavData Data =

{

{

{ "CCore" , "" , True , True },

{ "CCore 3-xx" , "D:/active/home/C++/CCore-3-xx/book/CCore.book.vol" , False , True },

{ "Sample" , "" , True , False },

{ "CCore 3-xx" , "D:/active/home/C++/CCore-3-xx/book/sample/CCore.book.ddl" , False , False }

},

0,

1

};

You can find the complete description here. DDL is

C-style,

typed,

commutative,

flexible,

polymorphe,

simple.

It can be conveniently used for representation of any kind of data with any level of internal connectivity. For example, this types are used to reprersent context-free grammars and LR1 state machines:

type AtomIndex = uint32 ;

type SyntIndex = uint32 ;

type KindIndex = uint32 ;

type ElementIndex = uint32 ;

type RuleIndex = uint32 ;

type StateIndex = uint32 ;

type FinalIndex = uint32 ;

struct Lang

{

Atom[] atoms;

Synt[] synts;

Synt * [] lang;

Element[] elements;

Rule[] rules;

TopRule[] top_rules;

State[] states;

Final[] finals;

};

struct Atom

{

AtomIndex index;

text name;

Element *element;

};

struct Synt

{

SyntIndex index;

text name;

Kind[] kinds;

Rule * [] rules;

};

struct Kind

{

KindIndex kindex; // index among all kinds

KindIndex index; // index in synt array

text name;

Synt *synt;

Element *element;

TopRule * [] rules;

};

struct Element

{

ElementIndex index;

{Atom,Kind} * elem;

};

struct Rule

{

RuleIndex index;

text name;

Kind *result;

type Arg = {Atom,Synt} * ;

Arg[] args;

};

struct TopRule

{

RuleIndex index;

text name;

Rule *bottom;

Kind *result;

type Arg = {Atom,Kind} * ;

Arg[] args;

};

struct State

{

StateIndex index;

Final *final;

struct Transition

{

Element *element;

State *state;

};

Transition[] transitions;

};

struct Final

{

FinalIndex index;

struct Action

{

Atom *atom; // null for (End)

Rule *rule; // null for <- ( STOP if atom is (END) )

};

Action[] actions;

};

And more samples:

int a = 10 ;

int * pa = &a ;

text [a] B = { "b1" , "b2" } ;

text [] C = { "c1" , "c2" } ;

struct S

{

text name = "unnamed" ;

int id = 0 ;

};

S record = { "" , 10 } ;

,:

int a = 10 ;

int * pa = &a ;

int b = *pa ; // 10

int[10] c = {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9} ;

int * pc = c+5 ;

int d = *pc ; // 5

int e = pc[2] ; // 7

int l = pc - c ; // 5

,:

type Ptr = {int,uint} * ;

int a = 1 ;

uint b = 2 ;

Ptr ptr_a = &a ;

Ptr ptr_b = &b ;

DDL is not intended for the manual data edition. Normally DDL files are generated by software and used by another software. It is a Soft-to-Soft language. You can think about it as a “universal data assembler”. I am lovely using DDL for many years for different purposes:

configuration files,

complex data files, like shown above,

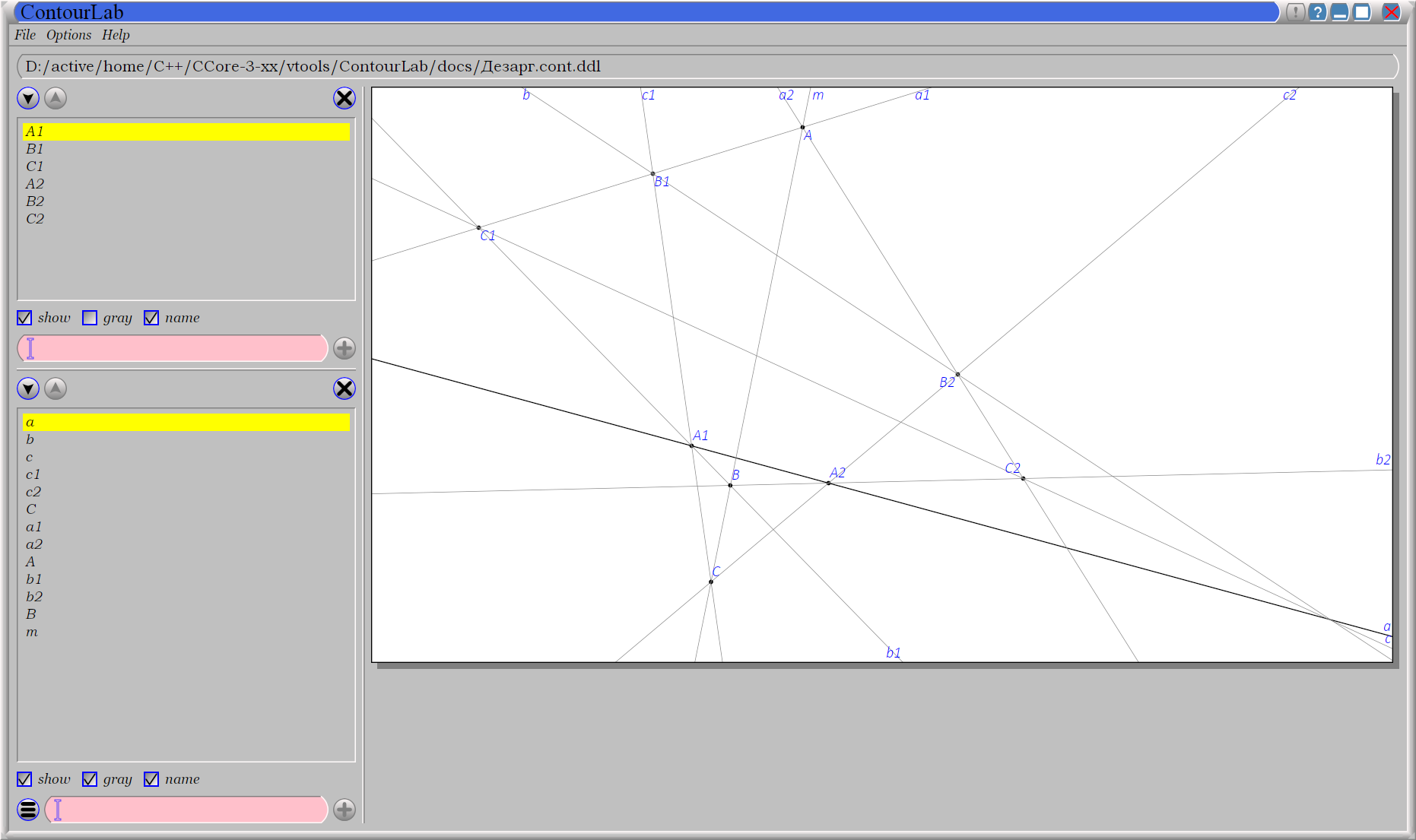

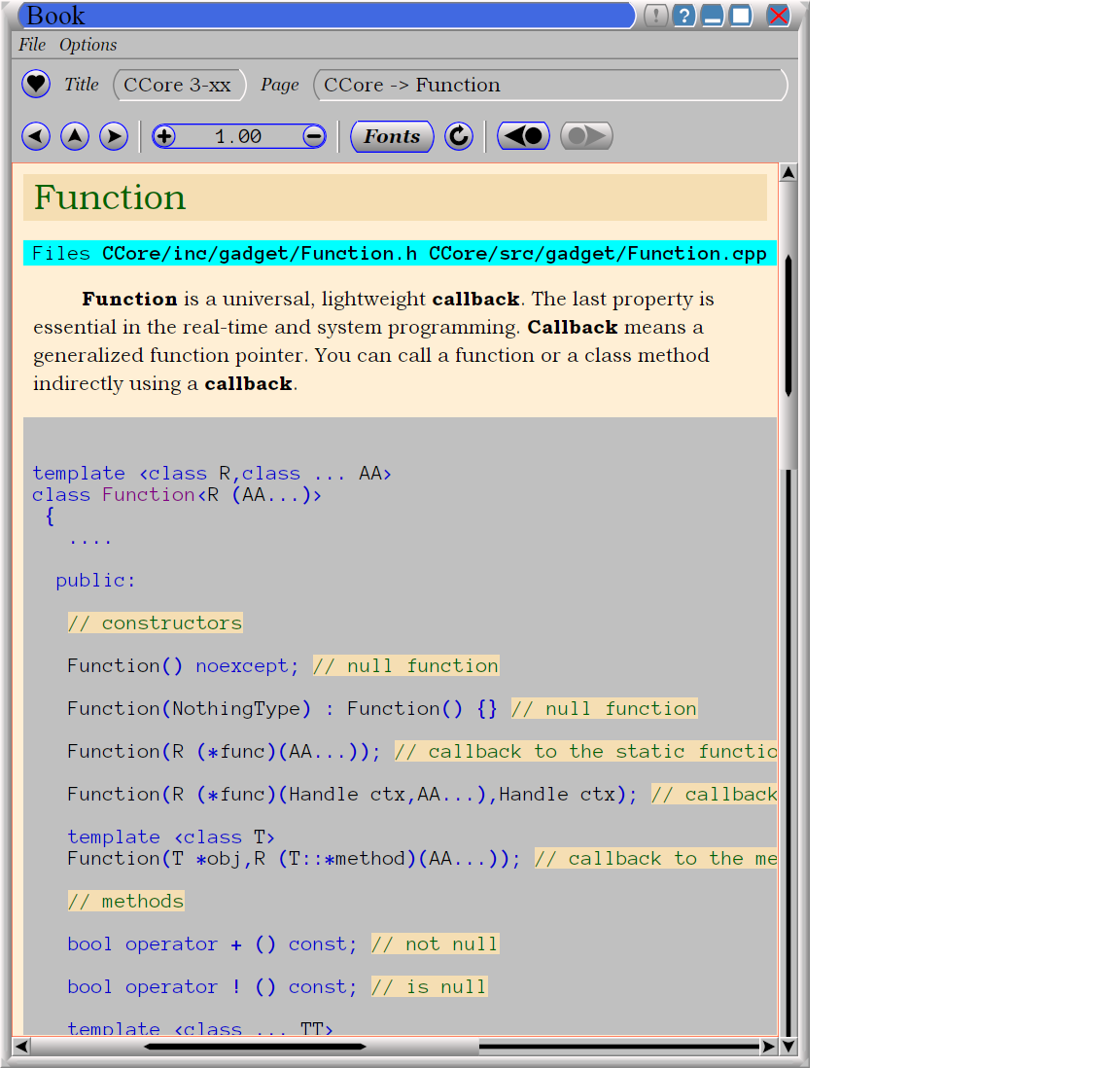

Book files, this is a latest GUI component, developed to represent formatted text:

So I advise everybody learn and use it in your projects. You will be loving it too! Printing DDL files is easy, you can do it using Printf(). To load data from DDL files, however, you need a library. CCore contains components and tools to do it, but you may develope your own, using CCore implementtaion as a reference design.

Synchronization¶

To develope multi-thread applications a good set of synchronization primitives is required. CCore defines the following such set:

Mutex,

Sem(aphore),

Event,

MultiSem,

MultiEvent,

AntiSem,

ResSem.

Mutex is a usual resource lock synchronization class:

class Mutex : NoCopy

{

....

public:

explicit Mutex(unsigned spin_count=MutexSpinCount());

explicit Mutex(TextLabel name,unsigned spin_count=MutexSpinCount());

~Mutex();

void lock();

void unlock();

unsigned getSemCount();

using Lock = LockObject<Mutex> ;

};

Sem is a usual semaphore:

class Sem : public Funchor_nocopy

{

....

public:

// constructors

explicit Sem(ulen count=0);

explicit Sem(TextLabel name,ulen count=0);

~Sem();

// give

void give();

void give_many(ulen dcount);

// take

bool try_take();

void take();

bool take(MSec timeout);

bool take(TimeScope time_scope);

// functions

Function<void (void)> function_give() { return FunctionOf(this,&Sem::give); }

};

CCore synchronization objects have two main kind of methods: giving and taking. Taking methods may block execution of the calling thread. So they usually have several variants: without timeout, with a timeout in milliseconds, with a timeout as a TimeScope, and a try variant with the “immediate” timeout. If a taking method with a timeout is failed, it returns false. Giving methods does not block, inversely, they may release a blocked on this synchronization object thread. And such methods comes with a callback. So you may call these methods indirectly using a light-weight callback Function<>.

TimeScope is a special method of the specifying a timeout. It starts at the moment, the object of this type is created, and lasts for the given period of time:

class TimeScope

{

MSecTimer timer;

MSec timeout;

public:

explicit TimeScope(MSec timeout_=Null) noexcept : timeout(timeout_) {}

void start(MSec timeout_)

{

timer.reset();

timeout=timeout_;

}

bool nextScope();

bool nextScope_skip();

MSec get() const

{

auto t=timer.get();

if( t >= +timeout ) return Null;

return MSec(unsigned( +timeout - t ));

}

};

It is very useful if you want to timed a combination of blocking calls:

void func(TimeScope time_scope)

{

op1(time_scope);

op2(time_scope);

op3(time_scope);

}

void func(MSec timeout)

{

TimeScope time_scope(timeout);

op1(time_scope);

op2(time_scope);

op3(time_scope);

}

Event is a binary semaphore:

class Event : public Funchor_nocopy

{

....

public:

// constructors

explicit Event(bool flag=false);

explicit Event(TextLabel name,bool flag=false);

explicit Event(const char *name) : Event(TextLabel(name)) {}

~Event();

// trigger

bool trigger();

// wait

bool try_wait();

void wait();

bool wait(MSec timeout);

bool wait(TimeScope time_scope);

// functions

void trigger_void() { trigger(); }

Function<void (void)> function_trigger() { return FunctionOf(this,&Event::trigger_void); }

};

MultiSem is a set of semaphors. This class is vital, if you need to handle events from multiple sources. For example, if you have to handle device interrupts and user requests in a device driver. Or to manage multiple networks connections. And so on:

template <ulen Len>

class MultiSem : public MultiSemBase

{

....

public:

MultiSem();

explicit MultiSem(TextLabel name);

~MultiSem();

};

class MultiSemBase : public Funchor_nocopy

{

....

public:

// give

void give(ulen index); // [1,Len]

// take

ulen try_take(); // [0,Len]

ulen take(); // [1,Len]

ulen take(MSec timeout); // [0,Len]

ulen take(TimeScope time_scope); // [0,Len]

// give<Index>

template <ulen Index> // [1,Len]

void give_index() { give(Index); }

// functions

template <ulen Index>

Function<void (void)> function_give() { return FunctionOf(this,&MultiSemBase::give_index<Index>); }

};

When you use MultiSem, you give some index (of event), take() returns an available index in the round-robing manner.

MultiEvent is a set of events. It is similar to the MultiSem, but designed based on Events, not Sems:

template <ulen Len>

class MultiEvent : public MultiEventBase

{

....

public:

MultiEvent();

explicit MultiEvent(TextLabel name);

~MultiEvent();

};

class MultiEventBase : public Funchor_nocopy

{

....

public:

// trigger

bool trigger(ulen index); // [1,Len]

// wait

ulen try_wait(); // [0,Len]

ulen wait(); // [1,Len]

ulen wait(MSec timeout); // [0,Len]

ulen wait(TimeScope time_scope); // [0,Len]

// trigger<Index>

template <ulen Index> // [1,Len]

void trigger_index() { trigger(Index); }

// functions

template <ulen Index>

Function<void (void)> function_trigger() { return FunctionOf(this,&MultiEventBase::trigger_index<Index>); }

};

AntiSem is a “gateway”. A thread can wait on this synchronization object until the internal counter of the object becomes below the defined level (0 by default). This synchronization object is useful for waiting of completion of multiple activities (like completion of multiple tasks) or releasing of number of resources:

class AntiSem : public Funchor_nocopy

{

....

public:

// constructors

explicit AntiSem(ulen level=0);

explicit AntiSem(TextLabel name,ulen level=0);

~AntiSem();

// add/sub

void add(ulen dcount);

void sub(ulen dcount);

// inc/dec

void inc() { add(1); }

void dec() { sub(1); }

// wait

bool try_wait();

void wait();

bool wait(MSec timeout);

bool wait(TimeScope time_scope);

// functions

Function<void (void)> function_inc() { return FunctionOf(this,&AntiSem::inc); }

Function<void (void)> function_dec() { return FunctionOf(this,&AntiSem::dec); }

};

ResSem is a hybrid of ResSem and Sem:

class ResSem : public Funchor_nocopy

{

....

public:

// constructors

explicit ResSem(ulen max_count);

ResSem(TextLabel name,ulen max_count);

~ResSem();

// give

void give();

// take

bool try_take();

void take();

bool take(MSec timeout);

bool take(TimeScope time_scope);

// wait

bool try_wait();

void wait();

bool wait(MSec timeout);

bool wait(TimeScope time_scope);

// functions

Function<void (void)> function_give() { return FunctionOf(this,&ResSem::give); }

};

It has an internal counter, which remains in the range [0,max_count], where max_count is a ResSem counter limit. Initially the counter equals max_count. Like a usual semaphore, ResSem has take() and give() operations, but it has the additional “gateway” operation wait(), which blocks the calling thread until the counter gets back to its maximum value.

Packets¶

When we design a system level services, we need to serve a massive tide of requests, coming independently from multiple tasks. Consider, for example, a network service stack. Application level tasks issue requests to send network packets, each packet has a body and destination address. Each of this requests must be processed, address must be resolved, body must be updated, finally, packet comes to a network card driver, which sends it on the wire. To develope such subsystems some basic infrustructure is required. The whole subsystem is a set of processing entities, they send to each other packets, each packet is some data structure with attached completion routine. Once a packet is handled, it sends to a next processing unit, or completed. CCore contains such infrustructure, Packets, and number of devices, which provides various packet services. For example, AsyncUDPMultipointDevice sends and receives UDP packets:

class AsyncUDPMultipointDevice : public PacketMultipointDevice

{

....

public:

// constructors

static constexpr ulen DefaultMaxPackets = 500 ;

explicit AsyncUDPMultipointDevice(UDPort udport,ulen max_packets=DefaultMaxPackets);

virtual ~AsyncUDPMultipointDevice();

// PacketMultipointDevice

virtual StrLen toText(XPoint point,PtrLen<char> buf) const;

virtual PacketFormat getOutboundFormat() const;

virtual void outbound(XPoint point,Packet<uint8> packet);

virtual ulen getMaxInboundLen() const;

virtual void attach(InboundProc *proc);

virtual void detach();

....

};

Networking¶

CCore implements a set of packet-processing classes for network applications. To work with network an abstraction layer is used. It is presented with two abstract classes: PacketEndpointDevice and PacketMultipointDevice:

struct PacketEndpointDevice

{

// outbound

virtual PacketFormat getOutboundFormat() const =0;

virtual void outbound(Packet<uint8> packet)=0;

// inbound

virtual ulen getMaxInboundLen() const =0;

struct InboundProc : InterfaceHost

{

virtual void inbound(Packet<uint8> packet,PtrLen<const uint8> data)=0;

virtual void tick()=0;

};

virtual void attach(InboundProc *proc)=0;

virtual void detach()=0;

};

struct PacketMultipointDevice

{

virtual StrLen toText(XPoint point,PtrLen<char> buf) const =0;

// outbound

virtual PacketFormat getOutboundFormat() const =0;

virtual void outbound(XPoint point,Packet<uint8> packet)=0;

// inbound

virtual ulen getMaxInboundLen() const =0;

struct InboundProc : InterfaceHost

{

static const Unid TypeUnid;

virtual void inbound(XPoint point,Packet<uint8> packet,PtrLen<const uint8> data)=0;

virtual void tick()=0;

};

virtual void attach(InboundProc *proc)=0;

virtual void detach()=0;

};

First of them is used for point-to-point communications, second – for point-to-multipoint. The first case is typical for client applications, but the second – for the server ones. There are classes like UDPEndpointDevice to establish a communication using the UDP protocol.

CCore implements a set of new application-level network protocols like PTP. PTP is the “Packet Transaction Protocol”. This is a packet-based, reliable, transactional, parallel point-to-point protocol. It is best suited to implement an asynchronous call-type client-server interaction. PTP defines rules for two endpoints, one is the Server, another is the Client. These endpoints exchange raw data packets (byte packets). Client issues call requests, Server takes call data, processes it and returns some resulting data. From the Client perspective, it makes a function call. Function arguments is a byte range. Server “evaluates” the function and returns a result — another byte range. The meaning of data is out of scope PTP protocol, it is defined by an upper protocol level. Usually, Server may serve multiple Clients. From the protocol perspective all transactions are parallel and independent.